Menu

The “Treatment First” response required clients to progress through programs before qualifying for permanent housing.

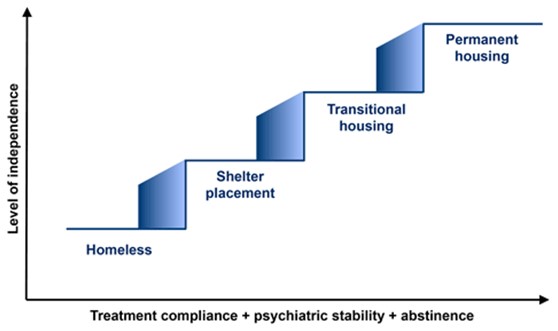

Homelessness services have typically operated according to the principle of a “linear continuum of care” predicated on an individual’s behaviour change and commitment to treatment before progressing to an idealised endpoint of independent living in permanent housing. The “Treatment First” response to homelessness typically required clients to commit to and progress through preparatory programs before qualifying for permanent housing placement.

This model of homelessness intervention has often been characterised as a “staircase”, starting with emergency shelters and ascending through transitional housing programs to demonstrate their housing readiness. The staircase’s top step is the attainment of permanent housing and a minimum of services required to maintain independent living. Services along the continuum are delivered in mandatory, supervised settings where clients are required to adhere to strict rules and demonstrate progress before qualifying as “housing ready” because they had been “trained” to live independently. Leading researchers in the homelessness space have described the staircase model as ‘a means to enhance an individual’s “housing readiness” whereby housing takes on a secondary function ‘subsequent to individual behaviour change.’

Figure 4: Staircase model of homelessness intervention: Source San Rafael

As the evidence base shows, the reality on the ground involves services heavily weighted toward the bottom of the continuum with limited access to anything beyond emergency shelter and temporary forms of accommodation. In turn, many people experiencing homelessness have struggled to progress beyond the lowest steps. Drawing on these limitations, leading commentators have critiqued the staircase model as an institutional circuit where ‘some never got beyond that first step, some skipped steps, and far too many fall off the “staircase.”’ (Padgett, Henwood et al. 2016, 7).

Research examining the staircase model of homelessness intervention applied to Australian, European and North American contexts has highlighted the following critical limitations:

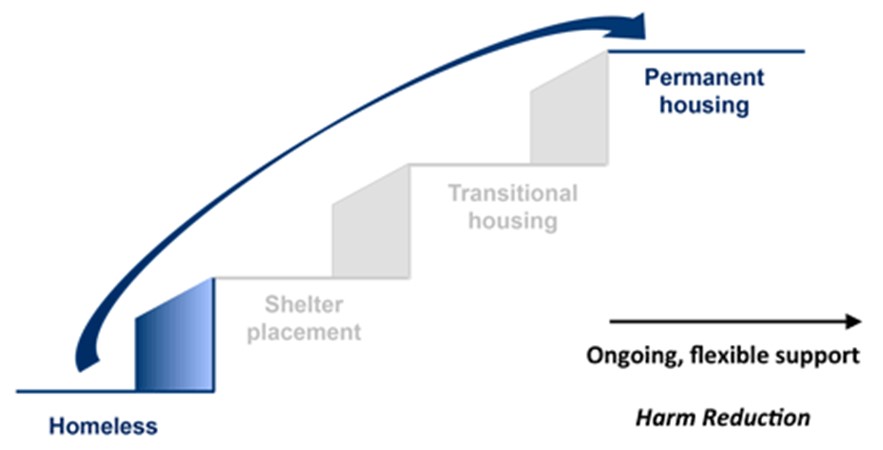

By way of contrast, the Housing First approach prioritises immediate permanent housing as the cornerstone of homelessness intervention, bypassing the need to complete a series of ‘steps’ to access a safe, secure place to call home. Put differently, housing is positioned as a starting point rather than an end goal.

Figure 5: Housing First model of homelessness intervention: Source San Rafael